This review discusses racial and sexual violence. A lot. And make a reference to gross stuff with poop.

“Some people need sun, clear nights, cool breezes, warm days—” I said.

“They can’t live in Bellona,” Tak went on. “In Helmsford, I knew people who never walked further than from the front door to the car. They can’t live in Bellona. Oh, we have a pretty complicated social structure: aristocrats, beggars—”

“Bourgeoisie,” I said.

“—and Bohemians. But we have no economy. The illusion of an ordered social matrix is complete, but its spitted through on all these cross-cultural attelets. It is a valuable city. It is a saprophytic city–It’s about the pleasantest place I’ve ever lived.”

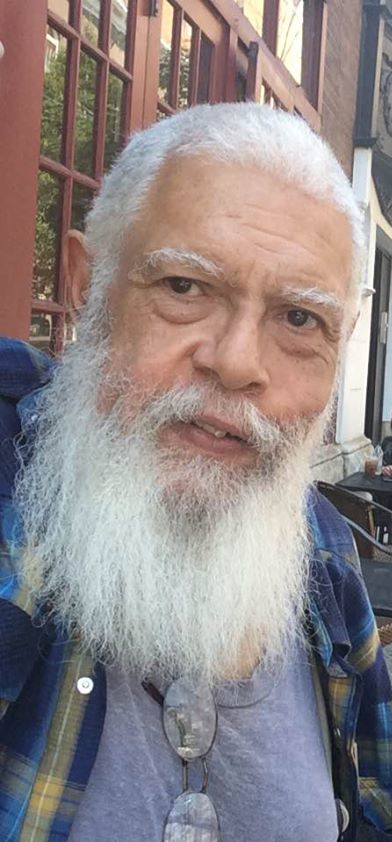

Samuel Delaney, Dhalgren

“When Dhalgren came out, I thought it was awful, still do… I was supposed to review it for the LA Times, got 200 pages into it and threw it against a wall.”

Harlan Ellison

In times of crisis, we look backwards for the ideas and leaders we need to transform the present. Ideas, intellectuals, visionaries, artists, philosophers are as strings in a vast sitar: when an idea in the present is plucked, a whole host of others from the past vibrate in sympathy. This is unfortunately as true for MAGAs as it is for the visionaries working to resurrect Martin Luther King Jr’s Poor People’s Campaign or 70’s black feminism.

I started reading Samuel Delaney’s 800-page epic Dhalgren because he fascinates me as someone who made space for himself in a sci-fi world that did not want him because of his race and his sexuality, and because he seemed to embody a fearless self-expression that is rare in any writer at any time. While I have seen his work mentioned in the context of black queer writers who brought the physicality of sex into the forefront of their work like Octavia Butler and Audre Lorde, and ideas from 1970’s revolutionary movements in general, it seems like Delaney’s work is more respected than read.

Dhalgren is not easy to read. The novel’s protagonist, Kid, experiences memory loss, bizarre dreams, and psychotic breaks, all narrated in a formally experimental, stream-of-consciousness style. Episodes blur into incoherence without resolution, characters’ names change throughout the book, and trying to imagine a geography is a fool’s errand. Delaney himself compared the novel to a Necker cube—a simple graphic cube that seems to shift orientation by redirecting your perspective, but neither can be said to be the “right” answer. I was able to make headway once I surrendered to the feeling of being lost in the text and decided to forego trying to decode each line. Slowly, Bellona, USA, came into focus.

Bellona is a large city, on the scale of Chicago or Philadelphia, somewhere in the midwest, in which something terribly strange has happened. Communications with the outside has been disrupted, no tv or radio signals make it into the city, there are only a few gateways to get in or out, and parts of the city have been destroyed, as through there were an attack or a bombing. Out of a city of millions, only some thousands remain. Those who remain scavenge food and supplies from abandoned stores, squatting in apartments and carrying on some version of their life before. There are hippies that live in a commune in the park, with utopian visions of rebuilding. A small number of middle-class characters try to carry on their routines despite increasingly ridiculous obstacles, commuting to abandoned office buildings and enjoying family dinners made of dwindling supplies. There is a Clockwork Orange-style hyper-violent street gang that lives communally and dominates the less weak on the strength of their weapons and the strange digital shields that they wear, which make them appear to be large, colorful, holographic animals. There is an apocalyptic cult, centered around a hyper-sexual, predatory black man named George Harrison, that plasters posters of his genitals around Bellona. Finally, there is a small group of remaining aristocracy centered around Calkins, the editor of a bizarre newspaper in which the dates and day of the week are random, and which is one of the few points of reference that cut across all of the social groups in Bellona.

We meet Kid at about the same time as he enters Bellona. He does not remember his name or his past and does not know why he is drawn to the place. The narrative is loose, basically a picaresque, with some metafictional elements as Kid picks up a notebook filled with some half-finished poems and begins to re/write them. Over the course of the story, Kid rises from naive outsider to leader of the Scorpions gang, to a larger-than-life figure that all of Bellona becomes fascinated by.

All of the things that make Dhalgren difficult to read make it impossible to tidily suggest what it might be about. There are some questions that clearly interest Delaney, however: What keeps society going when there is no possibility of economic growth or a future? How do hierarchies change when the outside world can neither influence the culture nor enforce power structures? Would a world in which everyone was free to express their sexual desire be dystopian or utopian? What is good writing anyway? How do you write about sex with no referent to shame? The images and textures that seem to fascinate Delaney such that they shoot through his writing include the slightly gross underside of sexuality, the ripe genitals and fluids and wounds and scars; the way that white Americans view and talk about black Americans, especially their sexual fascination with them; mental illness, psychiatric hospitals, and thought control; predatory and nonconsensual sex; classical mythology; violence that comes out of interpersonal disrespect; and this incredible vocabulary (I have a pretty large vocabulary, and I was constantly looking up words while reading).

Delaney’s idea of how society responds to collapse basically boils down to this: people are who they are, and they will generally just keep going even if all of the environmental feedback that they get is sending the message that it is a doomed strategy. This is my point of reference, probably not Samuel Delaney’s (although it certainly could have been), but I kept thinking about Pat Frank’s 1959 novel Alas, Bablyon, in which an isolated community survives following a nuclear attack. In that novel, neighbors throw off social hierarchies, band together, and pool resources and skills to start to make a new life for everybody. No such communal spirit emerges in Bellona. Delaney’s survivors maintain their social privileges, cling to familiar routines, and generally exist in a state of inertia slowly coming to rest. It is impossible to separate my reading of Dhalgren from the circumstances of my life: I recognized this futility in the various routines and rituals we have tried to bring into the coronavirus era. I am currently writing this from an empty office building in a massively depopulated downtown core.

On the other hand, there is no way for the formal institutions that backstop social hierarchies—no police, government authority, state or federal power—to enforce their norms within the boundary of the city, which creates a kind of utopia for transgressive sexuality. This is something so radical for its time (Dhalgren was published 6 years after the Stonewall Riot) but so normal now that I missed it at first. Nightlife in Bellona revolves around Teddy’s, the last remaining bar, in which a nude trans (this is a contemporary label, the character never discusses their own identity the way we would now) dancer is the nightly entertainment. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual pairings happen at Teddy’s, and even George, the avatar for predatory male heterosexuality, refers to queers with a mocking amusement and seems to enjoy their admiration of his posters. There’s a kind of attitude of presumptive bisexuality, to the the point of comic absurdity. Jack, an astronaut representing institutional, bourgeoise squareness, complains, “I was real nice to people; and people was nice to me too. Tak? The guy I met with you, here? Now he’s a pretty all right person. And when I was staying with him, I tried to be nice. He wants to suck on my dick, I’d say: ‘Go ahead, man, suck on my fuckin dick.’ And, man, I ain’t never done nothin’ like that before…I mean not serious, like he was, you know? Now, I done it. I ain’t sorry I done it. I don’t got nothin’ against it. But it is just not what I like all that much, you understand? I want a girl, with tits and a pussy. Is that so strange?

Kid meets Lana, a musician and teacher with more or less middle-class manners and attitudes, and Denny, a 15-year old hustler that seems to remind Kid of a younger version of himself. He has sexual relationships with them separately, and then they form a thruple, the relationship takes on a character of its own: “The scent of Denny’s breath, which was piney, joined Lanya’s, which reminded Kid of ferns.” I’m so hungry for representations of those forms of relationships that these were my favorite parts of the book. Delaney’s willingness to push way past the boundaries of taboo and taste make room for surprising moments of tenderness. When Kid intuits that Denny has a kink for degradation, he explores hitting and spitting and verbally humiliating him. After a few more times having sex, Denny nervously tells Kid—who has shown himself to be capriciously violent in the context of being the gang group leader—that he doesn’t particularly enjoy the physical roughness, and Kid instantly changes his approach, saving small bits of verbal humiliation for sexual encounters. In the context of musing about whether he subconsciously wants to get gang banged (when does that happen in a novel, even today?), Kid remembers to the night before where, even though he finds bottoming too painful to enjoy, he let Denny fuck him. “…the emotional thing there, anyway, was nice,” he remembers. His relationship with Layna is totally hands off and non-controlling. When a character tries to shame Kid for Lanya pursuing other relationships, Kid growls back, “if my old lady wants to fuck a sheep with a dildo strapped to her nose, that is largely her concern, very secondarily mine, and not yours at all. She can fuck anything she wants—with the possible exception of you. That, I think, would turn my stomach.”

This utopian picture of prejudice melting away in isolation does not extend to race. Dhalgren is saturated with racialized language language to an extent that is just extremely uncomfortable to me. N****r is used 80 times in the text, and there are several more epithets used commonly and casually. One of the most provocative uses of race in the novel is in the character of George Harrison, who embodies the racist stereotype of a buck from his physically dominant frame, hyper-sexuality, and predation. When Kid arrives, Bellona is recovering from a riot in the black neighborhoods precipitated by an incident where George rapes a 17-year old white girl, after which photos and an interview where George boasts at length about the rape are printed in the newspaper. A subplot moving through the novel involves various Bellonians keeping the girl from finding George, there’s an almost supernatural suggestion that if they were to get together then Bellona would really be finished. Delaney treats racial aggression, degradation, white consumption of the black body like Kara Walker’s plantation cutouts: symbols of erotic power that are literally unspeakable in civil society but hugely active on the subconscious of the culture.

I did not quite like Dhalgren. It is hard to read, it is often disgusting, a lot of it is very boring. I cannot write it off, though, because look at how much there is to think about! I was hoping to have this encounter with a radical black, queer voice, and I don’t think I was open enough, at the beginning, to understanding that Delaney and his work has it’s own set of interests apart from being a defanged mascot for me in the present. There is so much depicted in this novel that has become even more taboo in sexual culture now than it was at publication: racial fetishization, sex with teenagers, rape fantasies, gang rape, physical violence, piss drinking, scat eating. I don’t think that it would have occurred to Delaney back then that there was even a question that depiction could be different than endorsement. Right now we have this weird thing going on—an interim period where renegotiation of sexual norms that were not working for many people is going on, something that is more good than bad, on balance—where the distinction between erotic fantasy, public reputation, and real-life sexual conduct are all collapsing.

The kind of freedom that Delaney takes to simply explore, with his imagination, flies in the face of an ethic that says that perpetuating harmful images does real harm to vulnerable communities. Who has more right than he to make that judgement? He writes about gang raped, and he was gang raped by three men while hooking up with men across a language barrier. He writes disgusting things about black people, and he was the grandson of slaves with family stories of lynchings and various artists of the Harlem Renaissance who were friends with his father. Delaney understood the power of disgust, how closely the feeling resembles pornographic thrill.

Put another way: if a man and a woman fantasize about enacting and being raped, and the real-life consequence of their fantasy is a mutually consensual sexual encounter, and another couple admits no erotic fantasies but has bought into wild Q-Anon fantasies that there are pedophile rings and sex trafficking on every street in America, who are the perverts?

The swing from sexual repression to sexual liberation is a pendulum, and right now I cannot see what part of the arc we are in. It seems like there is a lot of pressure on queer conduct from the right wing, and a lot of pressure on the queer imagination from the left. I cannot imagine writing Dhalgren. I can barely admit to reading it seriously. I wish for myself the freedom of imagination that Delaney granted himself, and I wish for myself the fearlessness he had in sharing it. That, I feel confident, is something Dhalgren has to give to the present