Today was a good day, and one of the good things in it is that I came across this wonderful piece of writing called How To Do Nothing, by Jenny Odell. It’s a Medium post based on a speech she gave that she has expanded out into a book, which I immediately put a library hold on. It weaves together so many of the things I’ve been thinking about this year: how do we decide what is worth paying attention to, why do we all feel unbalanced by the internet and what has changed, how to communicate through the internet without being on the internet. The single, electrifying thought that Odell expands upon is this:

The function of nothing here, of saying nothing, is that it’s a precursor to something, to having something to say. “Nothing” is neither a luxury nor a waste of time, but rather a necessary part of meaningful thought and speech.

https://medium.com/@the_jennitaur/how-to-do-nothing-57e100f59bbb

Oh, I am so resistant to this idea.

There are some plants that only start to continue growing when old, dead matter is cut away. I am in a growth phase right now, and for every new idea tried, for every moment of understanding, there is also deep regret and loss for old ideas that I was just wrong about. One identity that I’m trying to let go of is as an “information junkie,” this persona who is curious and creative and constantly hungry for new information and stimulus. As a kid, I was always bored. I felt cut off from the information and cultural pathways that other people had access to because it was pre-broadband (if you were born after Google, pre-internet) and our household didn’t have a television set. Not even for VHS tapes. I went away to school in 9th grade, and one of the most precious freedoms I gained was internet access, and nothing was ever the same again, really. Since then, as each social network has been founded and attention has been fragmented and collated and monetized and optimized, there has only ever been the direction of more and more stimulation, more and more information. And over time, I think it’s drowned out my own thoughts.

Here’s the part that hurts, and here’s where the regret comes in: I thought that my ability to process and assimilate information was a rare gift. I thought that my peers who didn’t have the patience or stamina to sit down and power through a book, or the adults who didn’t seem to be in touch with news of the world or politics, or busy adults who didn’t have much time to read—all of these people deserved compassion, but they did not have the gift I had. In humble honesty, I thought that this made me better than other people. What I have to confront now is that other people may have just chosen to strike a different balance between what they give attention to in the wider world/culture, and what they give attention to in their own life.

This may seem like a small things, but there are implications that I’m very sensitive to. One is: if this is simply a different balance point struck, how satisfied am I with mine? Right now I am very unhappy with that balance—the stimulus I get from the internet and social media is addicting but makes me feel bad. Another is: if I have staked my identity on being a big brain, and the internet is a construct where the mind has complete dominance over body, what does it mean about me that I am washing out of being Extremely Online? Was I an animal the whole time, did I have bodily needs that a brain in a jar doesn’t have. Of course I was. A bleaker question: what did I miss out on while I was ignoring those needs?

Jenny Odell speaks to this, too:

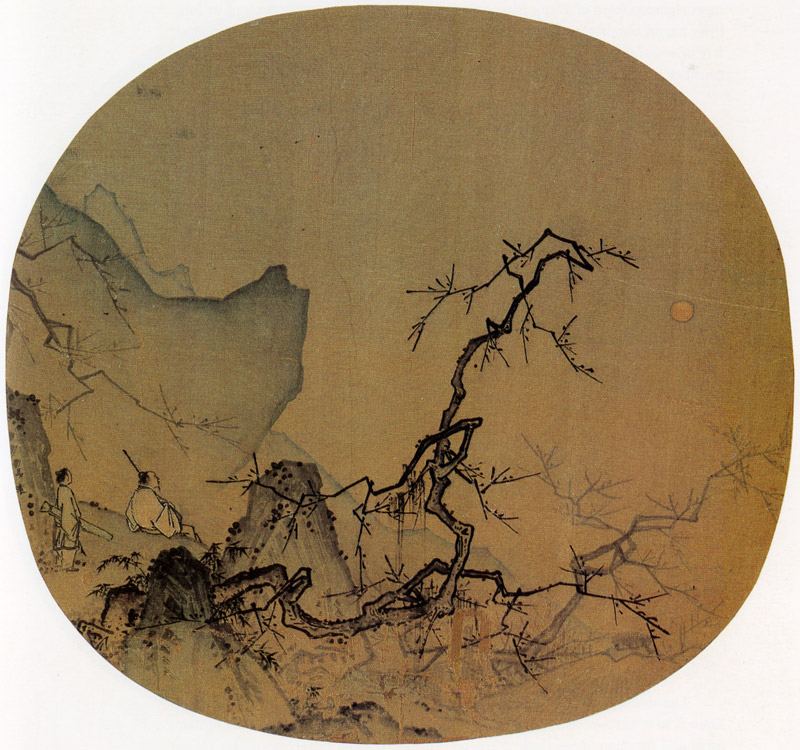

What is missing from that surreal and terrifying torrent of information and virtuality is any regard, any place, for the human animal, situated as she is in time and in a physical environment with other human and nonhuman entities. It turns out that groundedness requires actual groundedness, in the ground.

[…]

This is real. The living, breathing bodies in this room are real. I am not an avatar, a set of preferences, or some smooth cognitive force. I’m lumpy, I’m an animal, I hurt sometimes, and I’m different one day to the next. I hear, I see, and I smell things that hear, see, and smell me. And it can take a break to remember that, a break to do nothing, to listen, to remember what we are and where we are.

We have powerful forces that keep us from attending to the “soft animal of our body”: social platforms that don’t exist in real space and need our constant engagement with them to operate; our primate brain’s fear that if we don’t keep posting and ❤️ing, the troop will move on without us; and even our survival instinct:

In a situation where every waking moment has become pertinent to our making a living, and when we submit even our leisure for numerical evaluation via likes on Facebook and Instagram, constantly checking on its performance like one checks a stock, monitoring the ongoing development of our personal brand, time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on “nothing.” It provides no return on investment; it is simply too expensive.

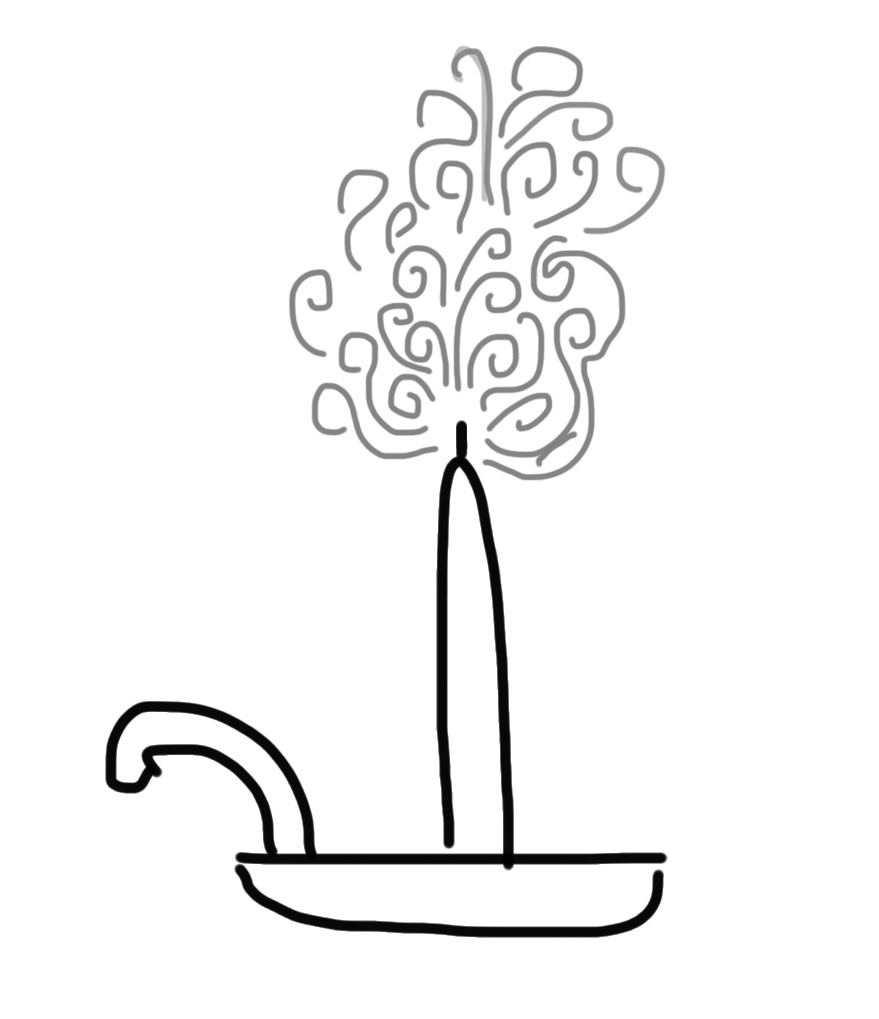

This is the biggest fear that I’m working through right now, as I’m changing my habits to incorporate more silence, more time for synthesis rather than stimulus. There’s an image I return to over and over again: the wonderful shapes in smoke after you blow out a candle. Move or talk too much, or if the room is too busy or drafty, and the smoke will just be blown around. But in stillness, in silence, the smoke makes wonderful patterns as it follows minute eddies of air. When I choose silence on a walk over browsing twitter as I walk, or listening to a podcast or music, I fear that I will become bored and it will have been a “waste of time.” An even deeper fear is that I will end up tuning into my own thoughts, and there will be nothing there.

But, of course, there always is something to be found there, if we’re brave enough to be patient. I hope. And if that turns out not to be the case, then I will set this idea down and try the next thing, which is all we ever can do anyway.