It is bi visibility day. One lovely thing about bisexuals is that—because it’s a tricky identity to wrap your head around—although folks come out as gay and lesbian according to a more or less microwave popcorn distribution centered around late high school and young adulthood, folks seem to steadily come out as bi as they assimilate that self-knowledge into the life and relationships they have.

I identified in high school as bisexual, but in college that didn’t last very long. I got really in my head about whether I was adopting the label because I was afraid to identify as gay, something that felt more taboo in the religious context I was raised in (more on that in a bit). In college I decided that because my attraction leaned heavily towards men, I might as well identify as gay and at the time it brought me a lot of satisfaction.

If the process of creating myself has been imperfect and absurd, coming to terms with my sense of desire has been downright chaotic. Boxes, labels… when we are looking for words to tell us who we are, they can be extremely helpful. Being named can help us feel less alone and make us feel like others who are like us have lived and have had meaningful lives. They are only ever shortcuts to self-understanding, though, and in the best case scenario, where they help you grow, one eventually grows out of them.

Once I put away some of my issues around body shame and being outside of the beauty ideal—a fucked up hierarchy that has so much power invested in it, particularly by gay men—I was able to rediscover my sense of play and exploration in regards to sexuality. It’s painful to think about how grim and serious my mental models for sex were 10 years ago. It was a hunger that could only be satisfied by metaphorically feeding off of, taking away from, someone else and (at best!) letting them feed off of you. Each the only one to see the true face of hunger. It was not a popular offer! Once I was able to trust others a little better and believe more in my own capacity to give pleasure, a whole different attitude that was light and playful and improvisatory and spontaneous and experimental opened up, and with that came better sex.

And an interest in exploring bodies other than cis men.

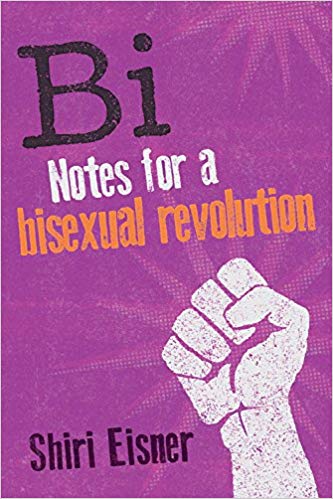

I think that I would have been fine with the (imperfect, contradictory) identity of “gay man who sometimes has sex with women sometimes and is pretty indifferent to the continuing decoupling of sex and gender,” but reading through Shiri Eisner’s Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution. In addition to going through some of the negative stereotypes of bisexuals in media—the vampire/serial killer/sociopathic/hedonist, the bi-until-graduation, I Kissed A Girl And I Liked It—Eisner points out that bisexuals are particularly destabilizing to patriarchal values because every deviation from its rules is a choice. It’s true that there are not very many visible bi male icons, and there is nowhere near the level of definition about what their (our) role is in society, much less than the roles of straight man or gay man.

I’m still figuring out what it means to be bi in practice. I’m happy to be visible, to be counted, to surprise anybody that has known me for a long time and people who form expectations instantly when they meet me alike. If I can open up the idea that the world around you is messier and more complicated than it looks on the surface, that’s a good day’s work done.