The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because I read that it was going to be adapted into a live action TV series, and that made me think about how few Japanese LGBT narratives and stories I knew. There are many manga and anime series that play around with homoerotic subtexts and images (including my current favorite, Yuri on Ice!!!), however—and, please understand that I have a very superficial understanding of Japanese culture—my perception is that many of those tropes are a slightly performative and desexualized playgrounds of desire for (mostly) straight preteen girls. The other examples of queer tropes in the culture are probably worse, which are the eroticized bisexual/lesbian chic like Ghost in the Shell, a melange of badass and charismatic characters that queer readers love but that were created for the pleasure of straight boys.

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because I read that it was going to be adapted into a live action TV series, and that made me think about how few Japanese LGBT narratives and stories I knew. There are many manga and anime series that play around with homoerotic subtexts and images (including my current favorite, Yuri on Ice!!!), however—and, please understand that I have a very superficial understanding of Japanese culture—my perception is that many of those tropes are a slightly performative and desexualized playgrounds of desire for (mostly) straight preteen girls. The other examples of queer tropes in the culture are probably worse, which are the eroticized bisexual/lesbian chic like Ghost in the Shell, a melange of badass and charismatic characters that queer readers love but that were created for the pleasure of straight boys.

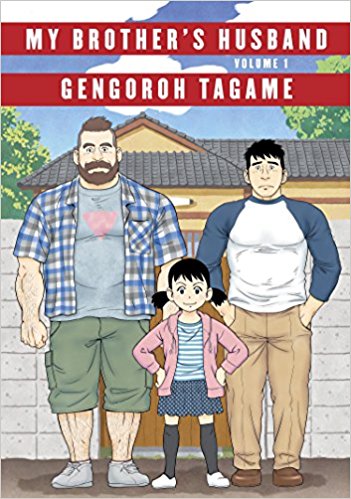

My Brother’s Husband is the story of Yaichi, who is forced to confront his feelings about his late twin brother, Ryōshi’s death and sexuality when Ryōshi’s widowed Canadian husband, Mike Flanagan, arrives at his doorstep to visit the town where the boys grew up. Mike is enthusiastically welcomed by Yaichi’s grade-school aged daughter, Kana, and this first of two volumes follows Yaichi through this brief visit as he struggles to balance his conflicted feelings about gay sexuality and his estrangement from his brother with his responsibility to his family and his love for his daughter.

The sensuality of bodies is present on every page, in every panel. Tagame describes himself in his twitter bio as a “gay erotic artist,” and most of his work (which has not been officially published in English translation) is sexually explicit stories featuring BDSM themes and big, muscly, hyper-masculine men presented as both figures of fear and figures of desire. My Brother’s Husband, at least through the first volume, is completely G rated, however the art style is shot through with his aesthetic. When Yaichi meets Mike, he is overwhelmed by the reality of Mike and his brother’s relationship, but he is also overwhelmed by Mike’s physical self, his size, his strength, his beard, the hair on his body.

There’s not a whole lot of action on the surface; this is a very quiet domestic drama with lots of talking, Yaichi’s internal dialogues as he explores his own discomfort with Mike, and getting lost in his memories and regrets. But underneath all that is a whole story expressed through touch and care for the body. When Mike first arrives, he wraps Yaichi in a bear hug and calls him brother.

This freaks Yaichi out, and he breaks out of the embrace and asks Mike not to call him that. As Yaichi explains to his daughter, Kana, “Japanese people don’t hug,” but he also admits to himself later that there is an undercurrent of homophobia and xenophobia to his response as well. Kana is completely unfazed by Mike, and is so excited to have a Canadian uncle that Yaichi’s standoffish attitude becomes rude by contrast. Yaichi’s comfort with Mike is shown without words through a growing physical intimacy, not through sex but through food, coffee and tea, the offer of a hot bath, a walk through a playground, and a shared visit to the gym.

I couldn’t help think about the deeper connection to Tagame’s erotic BDSM work. I only have an outsider’s understanding of that community, and on the kink spectrum, I think of myself as fresh vanilla bean ice cream (basic, but pretentious with an overinflated sense of self). That being said, I’ve always been fascinated to hear people share their experiences, and a big part of BDSM for a lot of people is that it provides a context for exploring pleasure and disgust, gender roles, toxic emotions, power dynamics, internalized homophobia, self-esteem, fight or flight responses, anxiety, sexual trauma, and a whole host of other really complex human experiences. Furthermore, it’s a way to cultivate an embodied understanding, completely different than understanding it intellectually. In other words, there’s a level of self-understanding that Tagame’s hypermasculine men can only access when they are having these heightened and risky sexual encounters. And in that same way, there is a level of acceptance of his dead brother that Yaichi can only get to, no matter what he thinks he thinks about him, that can only happen when he hugs his brother’s husband and feels love and connection and not discomfort.

This is what really blew me away, and why I remain completely emotionally lit up about this manga: in some ways this is a very quiet, very small-scale, and almost a didactic domestic drama. These are the type of queer stories that are told to straight society, and every time there is a movement for queer liberation, there is a need to teach the same lessons: we’re just like everyone else, love is love, who I am is bigger than who I fuck, etc. And they’re beautiful stories, and they’re important stories. But they are the queer stories that are always told before the queer queer stories get told. But Tagame has told this very tame queer story in a very queer way, and in that sense he has queered the queer acceptance narrative*. That’s so cool, and it’s incredible that at this time, when LGBT visibility is still in early formation in Japan, that this artist has created this work with such a clear sense of social purpose without ceding any of his individuality and sensibility.

*Postscript: Queering the Text

I wanted to briefly explain what I mean by “queering the queer acceptance narrative,” which is an extension of the concept of queering the text. Wikipedia has a truly dreadful definition:

Queering is an interpretive method used in historical or literary study. It is based on the re-appropriated term “queer“, used for LGBT issues, but used as a verb. “Queering” means to reevaluate or reinterpret a work with an eye to sexual orientation and/or to gender, by applying interpretive techniques from queer theory. An example of “queering” would be to reexamine the primary sources from the life of King Richard I of England, to search for evidence that he exhibited homosexual behavior or attitudes.

This definition gets a little bit right, but a lot of bits wrong. Queering is definitely an interpretive theory, but it is way more of a reinterpretation (or reinvention) than it is a reevaluation. The way that queering works is to take something, and to upend it by changing some of its underlying assumptions. It’s similar to Juvenalian satire (treating something elevated with the contempt and disdain of the low, and treating the low with the seriousness and gravitas of the elevated), and has roots in one of the early forerunners of queer identity, the invert (the man who acts like a woman and the woman who acts like a man). Queering as a praxis is one of the true essentials of queer culture and you can spot it everywhere. Its in the mock seriousness (but also actual seriousness) with which queer culture treats reality television and campy melodramas. It’s there in the cultivated banal tone in which we talk about high culture.

So when I say that My Brother’s Husband queers the queer acceptance narrative, what I mean is that Tagame has taken something that is familiar, targeted towards a homophobic straight reader, and almost commodified, and told the story in a way that has roots in something edgy, sexual, and boundary-pushing, he changes it into something new.

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because

Jeff Lemire – The Complete Essex County

Jeff Lemire – The Complete Essex County