In December 2012, Beck is set to release an “album” of sheet music. From the project page at publisher McSweeney’s:

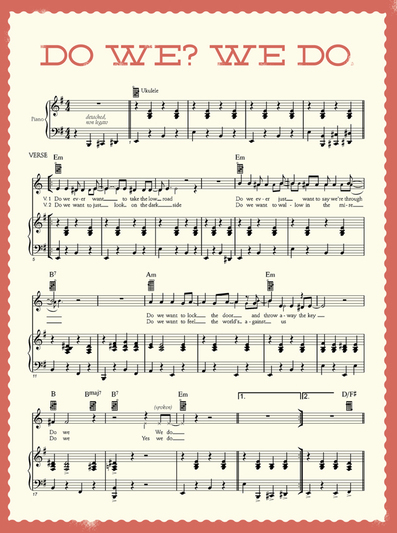

In the wake of Modern Guilt and The Information, Beck’s latest album comes in an almost-forgotten form—twenty songs existing only as individual pieces of sheet music, never before released or recorded. Complete with full-color, heyday-of-home-play-inspired art for each song and a lavishly produced hardcover carrying case (and, when necessary, ukelele notation), Song Reader is an experiment in what an album can be at the end of 2012—an alternative that enlists the listener in the tone of every track, and that’s as visually absorbing as a dozen gatefold LPs put together. The songs here are as unfailingly exciting as you’d expect from their author, but if you want to hear “Do We? We Do,” or “Don’t Act Like Your Heart Isn’t Hard,” bringing them to life depends on you.

This project is pushing every one of my music-nerd buttons. Of course it’s a gimmick, of course it’s a little precious. But we are going through a revolutionary time in music history, and this project is folding that history back on itself to bring back another time where the economic math of music was being recalculated.

Commercial music publishing is not a very important facet of the music business today. You can walk into any music store and see sheet music singles for Top 40 hits, but it’s also true that it’s easier to make a piano/vocal reduction of The Carpenter’s “We’ve Only Just Begun” than Ke$ha’s “TiK ToK.*” It’s hard to imagine from today’s perspective how disruptive a technology popular song sheet music was.

*Sheetmusicplus.com did have one hit for Ke$ha, surprisingly.

Notation (which is a kind of recording) introduced two important concept to music: the idea of a definitive version of a musical piece, and the idea of authorship of a musical piece. That first idea is inherent to the project of notation; just like speech, somebody might say things many different ways, or vary the way that they say it, but when you write something down, you’re only writing one thing down. The concept of authorship evolved over time. At first, as in Gregorian chant, a piece of music might be tied to the church or court that used it, the composer being anonymous. But as the composer evolved to become a separate artistic entity, there became only one Beethoven’s Fifth, and it was in one form and it was written by Beethoven.

But even through the invention of notation, even through the elevation of the composer, there was still no fixed concept of ownership of melody. Classical music constantly borrowed, stole, or arranged popular music or folk tunes; words were added to catchy classical melodies; people wrote new lyrics to popular tunes, dances and melodies disseminated and combined with each other. But when the commercial printing press combined with printed music, and the legions of newly middle-class women (usually) for whom a piano in the home and piano training were the markers of gentle society, you have a situation where independent songwriters can make a living by filling the void of new music. Remember, no record players. If you wanted music in the house, you made it yourself. And just as today, everybody wants new.

It’s impossible to overstate how influential these songs and songwriters were. Many of their compositions survive today, mistaken for folk songs: “Oh, Susanna” “Camptown Races” “Beautiful Dreamer” (Stephen Foster); “My Grandfather’s Clock” (Henry Clay Work); “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze” (Gaston Lyle); all of these were songs written and distributed as sheet music before the avent of recordings. Early recordings, in fact, were promotional material to sell sheet music! And even as revenue from the sale of recordings overtook that of sheet music, the dynamics of that era survive today through the power of the professional association for songwriters (ASCAP) and the large royalty payment that goes to the songwriter with every recording sold or licensed, often larger than that to the performer, largely because the songwriter holds copyright.

So let’s bring it back to Beck, and his song collection, and what it says about today.

First, I see it as a reminder that the economics of the music business are not set in stone, not given by God. The idea that I hand someone money for a physical object that contains a recording of a particular song by a particular artist is fairly new. Before that, I would pay money for a piece of sheet music that represented a particular song, but I was the performer. And before that I paid musicians, but there was no such thing as the definitive version of a song or a melody. Once, recordings were promotions for sheet music. Now, recordings may just be promotions for live shows. Of course this is going to change the quantity and the quality of the music we produce, but we’ll figure out how to make it work. Until something else comes along.

Second, I think this project is interesting in light of the conversations we’re having about remix culture and “audience” participation in works of culture. Think about it as a three-way tug-of-war between songwriter (or composer), performer, and audience. For all the talk of sampling, remixes, mash ups, YouTube covers, etc., we have to remember that the recording era had less audience participation than the sheet music era that preceded it. Beck is bringing music back to an era in which the act of consuming music was also an act of creation. It’s a nice reminder that, in an era where musicians are experimenting with interactive apps, or releasing workfiles to facilitate remixing, or even creating new music through fan videos, that the thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.