My mom called yesterday morning, greeting me with a Good morning. I groaned something back.

Oh, are you asleep? she asked.

No, I lied, I was up to read the Supreme Court decision. That wasn’t a lie. I had woken up to read the papers, so dulled by sleep that I just stared at my phone in confusion for thirty seconds before realizing that there were about ten apps that would have the news and I just had to pick one.

What was the decision about?

Perry vs. Schwarzenegger, you know, the Prop 8 case. Basically DOMA is gone and gay marriage is legal in California again. She said something in response and we agreed to talk later. As I drifted back asleep, I was struck with how different things were now, nearly five years after the Prop 8 election results disrupted my complacency about the tolerance of my state and my country.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∆ –––––––––––––––––––––––––

In the summer of 2008, I was 18 years old, and excited to be voting in my first election. I was—and am—the type of person to be excited by an election. Like many, I was surprised that May when the California Supreme Court first legalized gay marriage in the state. In the year and a half since I had first come out to a close friend, I engaged in a dedicated program of independent study of how to be gay. That study, however, mostly consisted of a ravenous consumption of the past fifty years of gay cultural artifacts, and I was uninformed about contemporary gay politics. The Court decision seemed a boon, and when the injunction against marriages followed and Prop 8 was put on the ballot, I barely noticed it. I assumed that the defeat of Prop 8 would be a formality, and California would assume its place as the great power of Western and liberal values and civil rights. That we had ceded such a place to the lesser states of Massachusetts and Iowa was an affront to state pride.

I was unforgivably complacent about that election. I vividly recall a long telephone conversation I had about the election with one of my high school teachers. I often talked about current events and politics with this teacher and, for a time, after leaving for college maintained the habit of calling him to shoot the breeze a couple of times a year. He was also, as I had come to understand, a deeply closeted gay man from three or four gay cultural generations previous to mine own (His present to me at my high school graduation—a DVD copy of the Merchant and Ivory adaptation of E.M. Forster’s Maurice—was an introduction to a lettered and more rarefied strain of gay culture than the Dan Savage columns and Queer as Folk episodes I had been pouring over). He kept insisting that the proposition would pass soundly. Even as opinion polls were showing a near even split in the state, he believed that people were afraid to express their prejudice to pollsters, but would behave differently in the voting booth. I insisted that it was impossible that such an initiative would pass in California—California!—of all places. I truly believed that while anti-gay prejudice was a significant force in other parts of the country, my state had, taken as a whole, grown out of that phase. I saw my teacher as a man scarred by the political fights of yesteryear, his memories blinding him to the new social reality. You’ll see in November, he said at the end of our conversation.

I saw.

It would take me a couple of years to read Randy Shilt’s And the Band Played On to learn that bureaucratic inaction can be the cruelest form of action, and that mass silence can equal mass death. It would take me a couple of years to read Eric Foner’s A Short History of Reconstruction to learn that civil liberties and the social protections of government can and have been taken away in this country. And it would take me a couple years of experiences of hearing the word faggot and becoming uncomfortable in and hyperaware of my surroundings, or hearing it shouted at me in the street, to learn that—like death in Arcadia—here, too, in one of the most liberal areas of the country, is prejudice.

––––––––––––––––––––––– ∆ –––––––––––––––––––––––––

I don’t know how many people have election rituals with their parents, but I have one with my mother. Every election, she fills out my absentee ballot for me while I’m on the phone, and we’ll usually talk through the ballot initiatives and candidates. She usually has more knowledge about local offices than I have, and I’m more willing to jump on the computer to research the statewide issues, and usually we vote the same way and for the same people. Sometimes, as with Prop 8 we differ. I don’t remember the specific content of my discussion with my mother. I do remember tiptoeing up to coming out to her and explaining that I had something of a personal stake in this issue, but never finding enough courage to say the words. Plus, the worst that could happen was that we would cancel each other’s votes out in an initiative fight that wasn’t going to pass anyway.

By the time the last California polls that night in November, the networks had all ready called the election for Obama and the atmosphere on campus was electric. An impromptu group of students were gleefully parading around campus playing will.i.am’s “Yes We Can” anthem with an unknowable admixture of irony and sincerity—or, if not sincerity, at least counter-irony. The memory I remember in most detail—noted for its subsequent entry into my personal Dorkiest Moments Hall of Shame—was inviting one of my friends to join me for a celebratory drink, just like a Big Man, leading both of us to uncomfortably sip straight citrus vodka from a plastic cup because I didn’t yet understand how alcohol worked. I also remember staying up into the early hours of Wednesday waiting for the full results for Prop 8 to come in. It was a couple hours after the networks and papers announced that it had passed when I finally accepted that the results of a few more precincts from Los Angeles County were not going to be enough to change the outcome.

Prop 8’s passage filled me with a deep sense of betrayal by my state and its voters, and also shame for myself and what I had not done. I knew that coming out to my mother would not have been a panacea. One vote wasn’t going to change the outcome of that election. But I knew that I didn’t just not come out to my mother, I didn’t post anything on Facebook, I didn’t make sure that people I knew voted, I didn’t email my relatives to come out to them and explain my position either. And it might be true that if I and everyone in my position had, maybe things would have been different.

I also understood immediately that I would be in for a long wait. As Ted Olsen and David Boies announced that they would be collaborating to bring a constitutional challenge to Prop 8, I waited. As, a few months later, Perry vs. Schwarzenegger was filed in California, I waited. As attorneys Olsen, Boies, Charles Cooper and Judge Vaughan Walker conducted what history will recognize as the trial of the century, I waited. As the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Walker’s decision, I waited. As the Supreme Court granted cert, I waited. As the Court conducted oral arguments last fall, I waited. Yesterday, that wait ended.

––––––––––––––––––– ∆ ––––––––––––––––––––

Prop 8 is dead. DOMA is dead. Code phrases like “not the marrying kind” or “confirmed bachelor” will lose their power, until some point in the future where those phrases will be identified with an note explaining their roots in pre-21st century prejudice against homosexual commitment ceremonies. And yet my joy in the political victory of my constituency and happiness for the people that this ruling will directly benefit is tempered by some feeling of ambivalence.

Some of my hesitation comes from a bad reason. This ruling is not very concrete for me yet. I don’t have a boyfriend, let alone one I would consider marrying. While this ruling has everything to do with the way that gays and lesbians are treated by civil society, marriage is a relationship entered in between one member of our community to another. Seen through that lens, this victory can seem like weak tea in the face of problems like employer and housing discrimination in the legal sphere, or simple prejudice in the social sphere in which we are directly asking those who disapprove of us for more tolerance—asking them to actively back down from their positions instead of leaving us alone while we marry each other. My hesitation also stems from a more nuanced understanding of how gay relationships have functioned outside of marriage, and the danger in trying obscure difference through shared conformities.

In this there is something unseemly: wedding boutiques expanding their offerings to cover same-sex weddings. Stores updating their gift registries. Jewelers advertising for his and his, and hers and hers. Articles about Washington, New York, and Los Angeles power couples consolidating their political and economic capital together. The faces of gay marriage, often wealthy white men, less often the not-wealthy, the nonwhite, the nonmen. Never all three. In all of this there is something unseemly. Gay men and women are being quickly assimilated into the iconography of this institution, and I cannot shake the sense that the community is trading something it doesn’t know the true value of for something it doesn’t need.

When I was first coming out to my friends, I kept the paranoia I developed in the closet about appearing “flaming,” or showing my interest in things that were “too gay.” Whenever I was confronted with any confrontational gay in news or media or life, be it the sissy, the queen, the activist, the sexual aggressor, I felt like I had to reassure my friends—but mostly myself—that I wasn’t going to be one of “those” gays. I was drawing a Chris Rock-like distinction between gay and faggot, and I didn’t want to be a faggot. In my mind’s eye, pictured my life as just like Straight Me’s life, just with shadowy figures of men instead of women. It took me longer to accept that Straight Me never existed, and therefore my life was going to look different from his. I recently came across Essex Hemphill’s poem “American Wedding,” written twenty-one years ago, which concludes:

I vow to you.

I give you my heart,

a safe house.

I give you promises other than

milk, honey, liberty.

I assume you will always

be a free man with a dream.

In america,

place your ring

on my cock

where it belongs.

Long may we live

to free this dream.

Past me would have been threatened by the eroticism of the poem, with the radical subversion of ritual. Present me thinks fuck yeah.

I am reminded of the first act of The Godfather, Part II, where drunken paisano Frank Pentangeli makes a scene at little Anthony Corleone’s confirmation party on the shores of Lake Tahoe by demanding that the whitebread bandleader play some Sicilian songs. Frank’s outburst punctures the event’s veneer of Anglo gentility. Certainly not Michael Corleone, probably not Anthony either, but Anthony’s children will look at the Tahoe party not as a symbol of the family’s social achievement, but as a demeaning reminder of the extent toward which the family was required to change itself simply to keep the economic and social standing it already possessed. Or maybe they won’t even miss the songs they’ve never heard. Conditional acceptance is being permitted to enter the mainstream. True acceptance is changing the definition of mainstream.

––––––––––––––––––––––– ∆ ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

I don’t want my reservations to obscure that I am very happy about yesterday’s rulings. Marriage is an invaluable institution to have access to, especially for couples with children. Even though I am nowhere near a marriage-level relationship—indeed, even if I never marry—this is a victory for me. DOMA was a sign of disrespect towards those gay couples who are married. Disrespect to those marriages is disrespect to the relationship the marriages encompassed. Disrespect to those to those relationships is disrespect to the type of relationship those couples have. Disrespect to the type of relationship is disrespect to those who want that type of relationship. Thus yesterday’s ruling was not just a victory for those in marriages a sign of respect for all of us who love like they love.

I’ve come to see the law as the shem in the mouth of the golem, both giving it power and power’s limits. Or as the lines in a pentagram, constraining the powerful demon within, the refinement of its shape reducing the possibility of escape or unintended action. Though I am always aware of the possibility of liberties being rolled back, I do also believe in the laws power, through precedent and time, to place certain incursions of liberty off the table. Yesterday’s ruling was one such precedent. It might be an incremental change, but in this small respect, the law has placed a part of my human dignity beyond debate. The hypocrite, the huckster, the two-bit fuckster, the douchebag, the crackpot, the fundie whackjob, all the bad actors that will someday take power, are forced to respect me in this small way. This is what makes me happy.

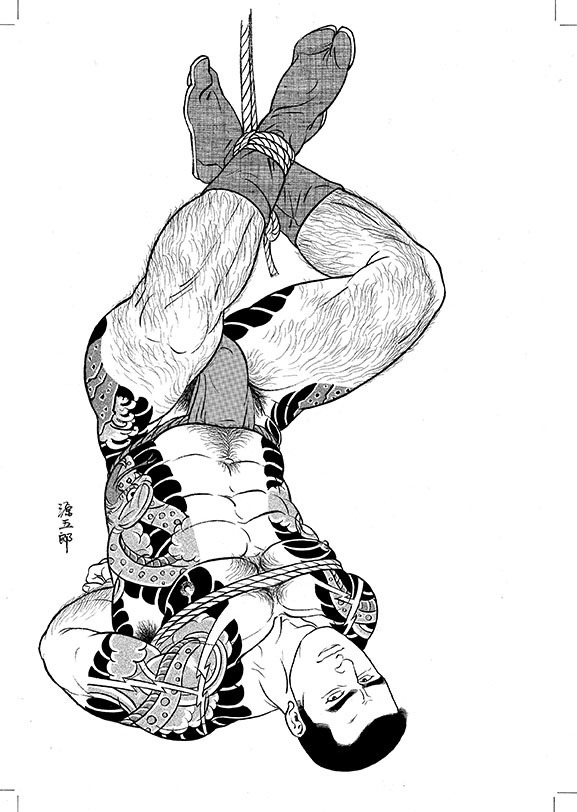

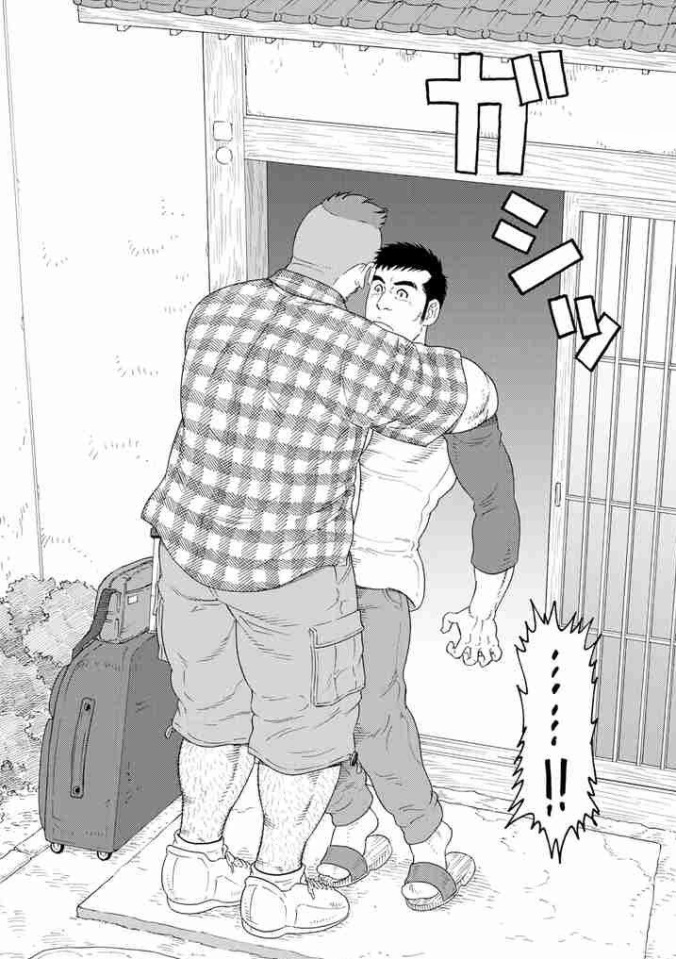

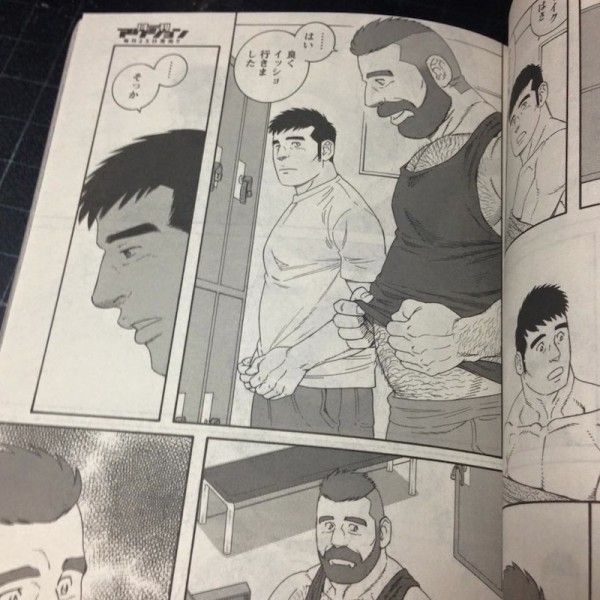

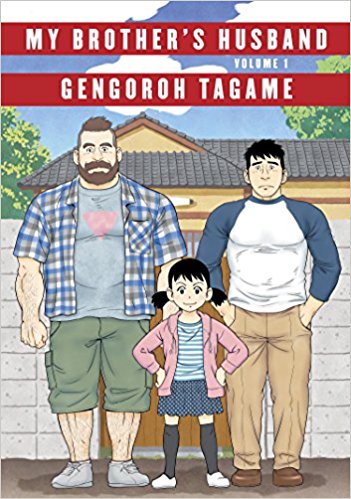

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because

The loveliest reading experience that exists is the experience of coming across the right book at the right time, and feeling so completely understood by it, and feeling like you completely understand it. I picked up My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, because